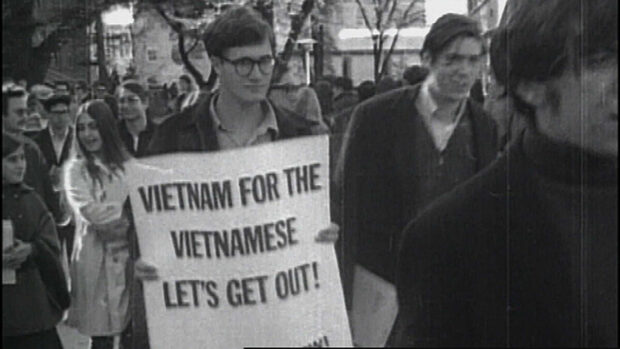

All of this has been drowned out since the fall of 1967 by the increasingly louder debate about the war in Vietnam. This had provoked criticism from the start, but mostly within academic circles and marginal groups of the New Left.

The Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) – a largely unknown group of a manageable number of student activists at the time – organized the first demonstration in April 1965 with at least 15,000 participants in front of the Washington Monument.

The same group had recently been part of the first teach-in at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, where professors and students were raving about the fact that many universities benefited not only from growing government investments in higher education but through Arms research participated directly in the war. This first teach-in caught on.

See also The Best Restaurants in the Meatpacking District: Add this to Your List

In the academic year 1965/66, seminars on Vietnam, some of which stretched over weeks, took place at more than a hundred universities. The spark jumped in 1966/67 and reached wider circles through church groups such as CALCAV, which had provided a forum for Riverside Church Speech.

The mood turned at the end of 1967. Not only the “New York Times”, but also “Time” and the “Washington Post” took increasingly critical positions on Vietnam on their opinion pages. Members of the intellectual and cultural elite are now increasingly distancing themselves from the war, although surveys show that the population continues to support it.

At the same time, the intensity of the protest increased. Three weeks after the event at Riverside Church, King marched at the head of more than 100,000 people from Central Park to the United Nations headquarters on the East River. A similar large protest took place in San Francisco. A march from the Lincoln Memorial to the Department of Defense on the other side of the Potomac on October 21, 1967, received massive attention. The march on the Pentagon also made history as a pictorial icon due to the photogenic juxtaposition of protesters and military police on the steps of the then freely accessible Pentagon.

In the fall of 1967, Johnson could no longer ignore the antiwar movement. His public appearances were disrupted by demonstrators. Close associates like Defense Secretary McNamara turned their backs on him. He had once confidently predicted the breaking of the Vietnamese resistance in view of the huge technological superiority of the USA.

In the fall of 1967, he repeated his warning internally that the war could no longer be won militarily and announced his resignation. Johnson in turn, who did not make his decision easy for himself, asked the wise men mentioned for advice. All, with the exception of ex-Deputy Secretary of State George Ball, recommended sticking to the chosen course. At a press conference in late November, General Westmoreland gave a broad account of the military progress made in fighting the enemy and said that the “light at the end of the tunnel” could be seen. This formulation fell on the administration’s feet at the end of January 1968.

Completely unexpected for the average media consumer, during the Tet offensive, the military enemy penetrated into the South Vietnamese cities and even into the sanctuary of the US embassy in Saigon. Although Tet ended in a bloody debacle for the Vietnamese Liberation Front, the communists achieved a psychological victory. Because Johnson and the US military leadership lost their credibility in the eyes of the media and many Americans.

Annual dates are arbitrary turning points in the flow of time. But in retrospect, years often acquire their own character, their own textuality written in numbers. 1967 in the USA is less than 1968 a highly symbolic turning point because, despite the impressive moments, it lacks the very great drama and density of the narratives. The fact that 1967 was not an election year in America contributed to this.

But the chain of events that then led to the conservative turnaround and the election of Nixon began in the spring of 1967 when several lines of conflict broke out: King’s Riverside Church Speech exposed the breaks within the liberal consensus coalition by referring to the non-fulfillment of demands for social equality as causal with the war Linked Southeast Asia. The post-war liberalism, which had made civil rights laws possible, frayed.

In the fall, George Wallace took up a racist counter-attack. In the summer of 1967, with the massive commercialization of counter-culture, the “death of the hippie” and the epidemic of sexual violence in San Francisco, as well as quasi-military confrontations in the burning slums of large cities, several American dreams came to a brutal end. “Images of disorder” were grist to the mill of the conservatives.

See also Lower Manhattan: The Insider Guide of Financial Center of New York

By staying on course in Vietnam, Johnson undermined his domestic political agenda and thus his presidency. America couldn’t afford “more guns and butter” at the same time. The liberal consensus-building only collapsed in 1968. But clear cracks in the facade of this proud building became visible everywhere in 1967.

Like us on Facebook for more stories like this: